Building a Serverless AI Bartender - Part 2: Guest registration and live order updates

Questo file è stato tradotto automaticamente dall'IA, potrebbero verificarsi errori

In Part 1, I built the foundation for the AI cocktail assistant. Guests can browse the drink menu, I can manage drinks and upload images, and the system generates AI image prompts via EventBridge. But there's one problem: guests can't actually order anything yet.

That's what we're building in this post. I need three things to complete the ordering flow. First, guests need to be able to register without creating full accounts; remember, this project was built for a small house party, and asking people to verify emails and set passwords is too much. Second, we still need an authenticated order placement flow so people can submit and track their drink orders. Third, I want real-time updates so when I mark a drink ready, guests see it instantly on their phones instead of constantly refreshing.

So let's get building!

Why not just let anyone order?

The easiest solution would be to just let the order endpoint be completely public, with an API key. Anyone can submit orders without authentication. But that creates some problems that I don't want to have.

Without user identification, I can't track who ordered what. If three people order Negroni, how do I know which is which when they're ready?

From a security perspective, a completely open endpoint is asking for trouble. Anyone on the internet could spam orders. Even at a house party, I want some basic control.

The solution needs to balance security with convenience. Guests shouldn't jump through hoops, but I need enough control to make the system usable.

Guest registration with invite codes

For admins, meaning me, I use Amazon Cognito with full authentication: email, password, JWT tokens, the works. That makes sense for me managing the drink menu and viewing all orders. But it's overkill for party guests.

I wanted it to be as simple as possible, like a party invitation. The idea was to have guests enter a registration code, enter their name, and be up and running.

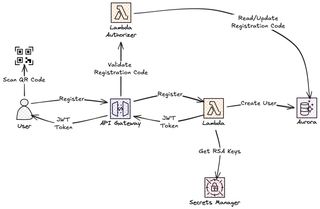

So how did I create that solution? Before the party, I generate a registration code. This code has an expiration date, valid for the day of the party, and a set number of times it can be used, making it possible to create a code valid for the expected number of guests plus a few extra. I can print the code as a scannable QR code, making it even easier to register. When guests arrive, they scan or enter the code along with their chosen name. The system validates the code, checks that it hasn't reached its maximum use or is expired, creates a user account, increments the code use count, and returns JWT tokens. The guest can now place orders. But wait—JWT tokens? Didn't I say no JWT tokens and sign up? Take it easy, I'm coming to that part.

This is how the registration was built.

The database schema

The registration system adds two new tables to the schema: app_users for guests and registration_codes for the invite codes.

CREATE TABLE cocktails.app_users (

user_key UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

username VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL,

created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP,

last_login TIMESTAMP,

is_active BOOLEAN DEFAULT true,

metadata TEXT DEFAULT '{}'

);

CREATE TABLE cocktails.registration_codes (

code UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP,

created_by VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

expires_at TIMESTAMP NOT NULL,

max_uses INTEGER NOT NULL,

use_count INTEGER DEFAULT 0,

notes TEXT

);I named the table app_users instead of just users since cocktails.users was already in use for admin authentication. Keeping them separate makes things much clearer.

The user_key is a UUID that identifies the guest, so we can have two "Sam"s at the party.

Registration codes also use UUIDs as the code value; this makes them "unguessable"—well, might be an exaggeration, but hard to guess anyway. Each code has a max_uses limit set at creation time, allowing the same code to register multiple guests. The use_count tracks how many times the code has been used.

Creating registration codes

I, as admin, create registration codes before the party through an admin endpoint. The Lambda function generates a UUID and sets the supplied expiration time.

def handler(event, context):

"""Admin endpoint - Create registration code."""

body = json.loads(event["body"])

expires_at = datetime.fromisoformat(body["expires_at"])

max_uses = body.get("max_uses", 1)

with get_connection() as conn:

with conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(

"""INSERT INTO cocktails.registration_codes

(created_by, expires_at, max_uses, notes)

VALUES (%s, %s, %s, %s)

RETURNING code, expires_at, max_uses""",

[event["requestContext"]["authorizer"]["userId"],

expires_at, max_uses, body.get("notes", "")]

)

result = cur.fetchone()

conn.commit()

return response(201, {

"code": str(result["code"]),

"expires_at": result["expires_at"].isoformat(),

"max_uses": result["max_uses"]

})The generated code looks something like this: f47ac10b-58cc-4372-a567-0e02b2c3d479. Now I can share this with guests however I want: text message, email, or printed as a QR code. For a house party with 20 guests, I might create one code with max_uses: 25 to account for plus-ones. For a larger event, I could create multiple codes per table or section.

The registration flow

When a guest registers, the system checks the supplied code and creates the account. The interesting part here is that this validation happens in two different stages. It starts with a Lambda authorizer that runs before the request even reaches the main logic, and then the endpoint itself verifies everything again. The authorizer's primary job is to make sure the code is real and hasn't hit its usage limit yet.

def handler(event, context):

"""Registration code Lambda authorizer."""

code = event["headers"].get("X-Registration-Code", "")

if not code:

return generate_policy("unknown", "Deny", event["methodArn"])

with get_connection() as conn:

with conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(

"""SELECT code FROM cocktails.registration_codes

WHERE code = %s AND use_count < max_uses AND expires_at > NOW()""",

[code]

)

if not cur.fetchone():

return generate_policy("unknown", "Deny", event["methodArn"])

return generate_policy(code, "Allow", event["methodArn"],

context={"registrationCode": code})Because the authorizer works at the API Gateway level, a bad code won't even make it to the registration Lambda. This setup is efficient because it prevents the registration Lambda from running for fake signups, preventing floods. After that initial check, the registration endpoint finishes the job by creating the user in the table and increasing the usage count on the code.

def handler(event, context):

"""POST /register - Create new guest user."""

code = event["requestContext"]["authorizer"]["registrationCode"]

username = json.loads(event["body"]).get("username", "").strip()

# Validate username

if not username or len(username) < 2 or len(username) > 50:

return response(400, {"error": "Username must be 2-50 characters"})

with get_connection() as conn:

with conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(

"""INSERT INTO cocktails.app_users (username)

VALUES (%s) RETURNING user_key, username""",

[username]

)

user = cur.fetchone()

# Increment code usage

cur.execute(

"UPDATE cocktails.registration_codes SET use_count = use_count + 1 WHERE code = %s",

[code]

)

conn.commit()

return response(201, {

"user": {"user_key": str(user["user_key"]), "username": user["username"]},

"access_token": generate_access_token(user),

"refresh_token": generate_refresh_token(user)

})The registration endpoint is idempotent in an important way. If the authorizer passes, we know the code is valid and hasn't reached its limit. If the Lambda fails halfway through due to a timeout or error, the use count isn't incremented so the guest can retry. Once the Lambda commits the transaction, the use count increases. When use_count reaches max_uses, the authorizer will reject future registration attempts with that code.

Self-signed JWT tokens

Now, back to the JWT tokens—I told you we were coming back to this.

After a successful registration, guests receive JWT tokens. But unlike the admin flow, which uses Cognito-issued tokens, guest tokens are self-signed. I generate them myself using RSA key pairs stored in AWS Secrets Manager.

Why self-signed instead of Cognito?

Cognito is a great service, but it's designed for long-lived users. If I used it here, I'd need to create user pool accounts, manage passwords, and deal with email verifications. That is a lot of overhead for a guest who is only there for a few hours.

Going with self-signed JWTs gives me the flexibility to control exactly what is in the token and how long it stays active. Guests do not need things like multi-factor authentication or password resets. They just need a way to prove they signed up so they can order for the night.

The catch is that I have to handle the validation myself. I need to manage an RSA key pair and write the verification logic in a Lambda authorizer. However, the process isn't that complicated, and I like having that level of control over the whole flow.

Creating access and refresh tokens

The registration Lambda generates two tokens: an access token and a refresh token.

def generate_access_token(user: dict) -> str:

"""Generate RS256 signed JWT access token."""

payload = {

"token_type": "access",

"user_key": str(user["user_key"]),

"username": user["username"],

"exp": int(time.time()) + (4 * 60 * 60) # 4 hours

}

return jwt.encode(payload, get_private_key_from_secrets_manager(), algorithm="RS256")

def generate_refresh_token(user: dict) -> str:

"""Generate cryptographically random refresh token."""

token = secrets.token_urlsafe(32)

token_hash = hashlib.sha256(token.encode()).hexdigest()

with get_connection() as conn:

with conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(

"""INSERT INTO cocktails.refresh_tokens (user_key, token_hash, expires_at)

VALUES (%s, %s, %s)""",

[user["user_key"], token_hash, datetime.utcnow() + timedelta(days=2)]

)

conn.commit()

return tokenThe access token is a JWT with a 4-hour expiration. Four hours is enough for a party but short enough that stolen tokens don't last forever. The payload includes user_key and username so downstream Lambda functions know who's making requests.

The refresh token is different. It's not a JWT, just a cryptographically random string. I store the SHA-256 hash in the database along with its expiration, 2 days. This lets guests keep their session alive across multiple app reopenings without needing to re-register.

The refresh token table

Refresh tokens are stored separately from users.

CREATE TABLE cocktails.refresh_tokens (

token_id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

user_key UUID NOT NULL,

token_hash VARCHAR(64) NOT NULL,

created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP,

expires_at TIMESTAMP NOT NULL,

last_used_at TIMESTAMP,

is_revoked BOOLEAN DEFAULT false,

revoked_at TIMESTAMP,

device_info TEXT

);Why hash the refresh token instead of storing it directly? Because refresh tokens are long-lived—if we can call 2 days long-lived. If someone gains database access, they could use stored tokens to impersonate users. By hashing, we ensure that even with database access, the attacker can't reconstruct the original tokens.

The is_revoked flag lets me invalidate tokens if needed. The device_info field stores metadata like browser user agent, useful for debugging or showing users where they're logged in.

Token refresh endpoint

When the access token expires, the frontend calls the refresh endpoint with the refresh token.

def handler(event, context):

"""POST /auth/refresh - Exchange refresh token for new access token."""

refresh_token = json.loads(event["body"]).get("refresh_token", "")

if not refresh_token:

return response(400, {"error": "refresh_token required"})

token_hash = hashlib.sha256(refresh_token.encode()).hexdigest()

with get_connection() as conn:

with conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(

"""SELECT rt.user_key, u.username FROM cocktails.refresh_tokens rt

JOIN cocktails.app_users u ON rt.user_key = u.user_key

WHERE rt.token_hash = %s AND NOT rt.is_revoked AND rt.expires_at > NOW()""",

[token_hash]

)

token_record = cur.fetchone()

if not token_record:

return response(401, {"error": "Invalid or expired refresh token"})

cur.execute(

"UPDATE cocktails.refresh_tokens SET last_used_at = NOW() WHERE token_hash = %s",

[token_hash]

)

conn.commit()

return response(200, {

"access_token": generate_access_token({

"user_key": token_record["user_key"],

"username": token_record["username"]

})

})This pattern is standard OAuth2-style token refresh. The refresh token never expires as long as it's used periodically. The access token expires frequently but can be renewed without re-authenticating.

The user authorizer

Order endpoints require authentication. The user authorizer Lambda validates the self-signed JWT access tokens.

def handler(event, context):

"""User JWT Lambda authorizer - validates self-signed tokens."""

try:

token = extract_bearer_token(event)

claims = jwt.decode(

token,

get_public_key_from_secrets_manager(),

algorithms=["RS256"],

options={"verify_signature": True, "verify_exp": True}

)

if claims.get("token_type") != "access":

return generate_policy("unknown", "Deny", event["methodArn"])

return generate_policy(

claims["user_key"], "Allow", event["methodArn"],

context={"userId": claims["user_key"], "username": claims["username"]}

)

except (jwt.ExpiredSignatureError, jwt.InvalidTokenError):

return generate_policy("unknown", "Deny", event["methodArn"])As I said, you can see, this isn't that complex. The Lambda authorizer, invoked by API Gateway, loads the public key from Secrets Manager, verifies the token signature with the PyJWT library, and checks the expiration. If everything passes, it extracts the user_key and username and passes them to the downstream Lambda function via the authorizer context.

Downstream Lambda functions don't need to parse JWT tokens themselves. The context is available at event["requestContext"]["authorizer"].

Caching the public key

One optimization worth noting is caching the public key. Loading it from Secrets Manager on every request would be slow and expensive. Instead, I cache it in a global variable.

_jwt_public_key = None

def get_public_key_from_secrets_manager() -> str:

"""Get JWT public key from Secrets Manager with caching."""

global _jwt_public_key

if _jwt_public_key is not None:

return _jwt_public_key

client = boto3.client("secretsmanager")

response = client.get_secret_value(SecretId="drink-assistant/jwt-keys")

secret = json.loads(response["SecretString"])

_jwt_public_key = secret["public_key"]

return _jwt_public_keyLambda execution environments are reused across invocations. The first invocation loads the key and caches it. Subsequent invocations in the same execution environment reuse the cached key. This reduces Secrets Manager API calls and improves latency in many cases—it's not perfect but for sure good enough.

Placing orders

With registration and authentication complete, guests can now place orders. The order endpoint is protected by the user authorizer.

The orders table

Orders are stored in the cocktails.orders table.

CREATE TABLE cocktails.orders (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

drink_id UUID NOT NULL,

user_key UUID,

status VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL DEFAULT 'pending',

created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW(),

updated_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW(),

completed_at TIMESTAMP

);The user_key links to app_users.user_key. The status field tracks the order lifecycle: pending, preparing, ready, or served. The completed_at timestamp is set when status reaches served.

Creating an order

The create order Lambda is straightforward. It verifies the drink is available—I don't want guests to order a Negroni if I ran out of Campari. Next, it creates the order record and returns the order details.

def handler(event, context):

"""POST /orders - Create new order for authenticated user."""

user_key = event["requestContext"]["authorizer"]["userId"]

drink_id = json.loads(event["body"]).get("drink_id")

with get_connection() as conn:

with conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(

"SELECT id, name FROM cocktails.drinks WHERE id = %s AND is_active = true",

[drink_id]

)

drink = cur.fetchone()

if not drink:

return response(404, {"error": "Drink not found"})

cur.execute(

"""INSERT INTO cocktails.orders (drink_id, user_key, status)

VALUES (%s, %s, 'pending') RETURNING id, status, created_at""",

[drink_id, user_key]

)

order = cur.fetchone()

conn.commit()

publish_order_created(user_key, event["requestContext"]["authorizer"]["username"],

order, drink["name"])

return response(201, {

"order": {

"id": str(order["id"]),

"drink_name": drink["name"],

"status": order["status"],

"created_at": order["created_at"].isoformat()

}

})Listing user orders

Guests can also fetch their complete order history.

def handler(event, context):

"""GET /orders - List orders for authenticated user."""

with get_connection() as conn:

with conn.cursor() as cur:

cur.execute(

"""SELECT o.id, d.name AS drink_name, o.status, o.created_at

FROM cocktails.orders o JOIN cocktails.drinks d ON o.drink_id = d.id

WHERE o.user_key = %s ORDER BY o.created_at DESC""",

[event["requestContext"]["authorizer"]["userId"]]

)

return response(200, {"orders": cur.fetchall()})The query joins orders with drinks to include the drink name in the response. Guests see "Negroni - pending" instead of a UUID.

Order status updates

This is the part I’m very excited about and one of the key elements in this part. While I was building the app, I realized there was a potential problem that would create a bad user experience. If you place an order and have no way of knowing the progress, you just end up coming over and bother me asking for your drink. That kind of manual checking really defeats the purpose of the app.

I knew I needed some form of live system from the start. The moment I mark a drink as ready on my end, the app on the guest's phone should update and notify. No polling and no refresh button needed.

Real-time updates are usually just pub/sub

When people talk about "real-time updates," what they usually mean from a technical perspective is a Pub/Sub (Publish/Subscribe) model. This is exactly why I chose AWS AppSync Events—it's a powerful pub/sub service that will let me push updates to users.

In a standard web app, the client has to ask for data (request/response). In a pub/sub setup, the client subscribes to a specific topic, like orders/{user_id}. Then, whenever a change happens on the server, the backend publishes a message to that topic. The pub/sub broker (in our case, AppSync Events) handles the heavy lifting of figuring out who is listening and pushing that message out to them instantly.

AppSync Events vs EventBridge

In Part 1, I used Amazon EventBridge for event workflows like generating AI image prompts. EventBridge is a great service when building event-driven applications. But EventBridge doesn't push events to client applications.

To implement a client pub/sub setup I will need to use Websockets in some form. The easiest way I have found to get a pub/sub setup over websockets is to use AppSync Events—now don't let the AppSync part in the name fool you. This is very different from AppSync API, which is a managed GraphQL API implementation. It's a bit unfortunate I think that the pub/sub implementation landed under AppSync as well.

AppSync Events handles connections, subscriptions, and broadcasting automatically. I just publish events from Lambda, and AppSync routes them to subscribed clients.

AppSync Events concepts

AppSync Events is built around three concepts.

Channels are like topics in a pub/sub system. Clients subscribe to channels to receive events. In my case, each user subscribes to orders/{user_key} to get updates about their orders.

Channel namespaces group related channels. I create a namespace called orders, and channels are created dynamically within it. When a user subscribes to orders/abc-123, AppSync automatically creates that channel if it doesn't exist.

Events are messages published to channels. When I update an order status, I publish an event to that user's channel. AppSync broadcasts it to all connected clients subscribed to that channel.

Pub/Sub design overview

The pub/sub setup with AppSync Events looks something like this.

Setting up AppSync Events

The CloudFormation creates an AppSync Events API with channel namespaces.

Resources:

EventsApi:

Type: AWS::AppSync::Api

Properties:

Name: !Sub "${AWS::StackName}-events-api"

EventConfig:

AuthProviders:

- AuthType: API_KEY

ConnectionAuthModes:

- AuthType: API_KEY

DefaultPublishAuthModes:

- AuthType: API_KEY

DefaultSubscribeAuthModes:

- AuthType: API_KEY

EventsApiKey:

Type: AWS::AppSync::ApiKey

Properties:

ApiId: !GetAtt EventsApi.ApiId

Description: API Key for AppSync Events

Expires: 1767225600 # Far future expiration

OrdersChannelNamespace:

Type: AWS::AppSync::ChannelNamespace

Properties:

ApiId: !GetAtt EventsApi.ApiId

Name: orders

SubscribeAuthModes:

- AuthType: API_KEY

PublishAuthModes:

- AuthType: API_KEY

AdminChannelNamespace:

Type: AWS::AppSync::ChannelNamespace

Properties:

ApiId: !GetAtt EventsApi.ApiId

Name: admin

SubscribeAuthModes:

- AuthType: API_KEY

PublishAuthModes:

- AuthType: API_KEYI use API key authentication for simplicity. In production, you'd use Cognito or IAM to ensure users can only subscribe to their own channels. But for a house party, an API key embedded in the frontend is sufficient.

I create two channel namespaces. The orders namespace is for user-specific order updates. Guests subscribe to orders/{their_user_key}. The admin namespace is for admin dashboard updates. I subscribe to admin/new-orders to see when new orders come in.

Publishing events from Lambda

When an order's status changes, the Lambda publishes an event to AppSync.

def publish_order_update(user_key: str, order: dict, drink_name: str):

"""Publish order status update to user's AppSync Events channel."""

try:

appsync_client.post(

action="publish",

apiId=os.environ["APPSYNC_API_ID"],

payload=json.dumps({

"channel": f"orders/{user_key}",

"events": [json.dumps({

"type": "ORDER_STATUS_CHANGED",

"order_id": str(order["id"]),

"drink_name": drink_name,

"status": order["status"],

"updated_at": order["updated_at"].isoformat()

})]

})

)

except Exception as e:

logger.error(f"Failed to publish: {e}")Publishing is fire-and-forget. If it fails, I log the error but don't fail the entire order update. The order status is saved to the database regardless. The worst case is the guest doesn't get a real-time notification and has to refresh manually.

Publishing new order events to the admin dashboard

When a guest creates an order, I also publish to the admin channel so I know immediately.

def publish_order_created(user_key: str, username: str, order: dict, drink_name: str):

"""Publish new order event to admin channel."""

try:

appsync_client.post(

action="publish",

apiId=os.environ["APPSYNC_API_ID"],

payload=json.dumps({

"channel": "admin/new-orders",

"events": [json.dumps({

"type": "NEW_ORDER",

"order_id": str(order["id"]),

"user_key": user_key,

"username": username,

"drink_name": drink_name,

"status": "pending",

"created_at": order["created_at"].isoformat()

})]

})

)

except Exception as e:

logger.error(f"Failed to publish: {e}")Now both the guest app and the admin dashboard get real-time updates. Guests see their order status change. I see new orders appear instantly.

Subscribing from the frontend

On the frontend, I use the AWS Amplify library to subscribe to AppSync Events channels.

First, configure Amplify with the AppSync Events API details.

import { Amplify } from 'aws-amplify';

Amplify.configure({

API: {

Events: {

endpoint: 'https://abc123.appsync-api.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/event',

region: 'us-east-1',

defaultAuthMode: 'apiKey',

apiKey: 'da2-xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx'

}

}

});Then subscribe to the user's order channel.

import { events } from '@aws-amplify/api';

function subscribeToOrderUpdates(userKey: string) {

const channel = events.channel(`orders/${userKey}`);

const subscription = channel.subscribe({

next: (event) => {

console.log('Order update received:', event);

// Update UI based on event type

if (event.type === 'ORDER_STATUS_CHANGED') {

updateOrderInUI(event.order_id, event.status);

if (event.status === 'ready') {

showNotification(`Your ${event.drink_name} is ready!`);

}

}

},

error: (error) => {

console.error('AppSync Events error:', error);

}

});

// Return unsubscribe function

return () => subscription.unsubscribe();

}The channel subscription uses WebSockets under the hood. When the Lambda publishes an event, AppSync pushes it to all connected clients subscribed to that channel. The next callback fires immediately when events arrive.

React hook for real-time orders

I wrapped the subscription logic into a React hook that manages the connection lifecycle.

import { useEffect, useState } from 'react';

import { events } from '@aws-amplify/api';

interface Order {

id: string;

drink_id: string;

drink_name: string;

status: 'pending' | 'preparing' | 'ready' | 'served';

created_at: string;

updated_at: string;

}

export function useRealtimeOrders(userKey: string) {

const [orders, setOrders] = useState<Order[]>([]);

const [connected, setConnected] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => {

if (!userKey) return;

const channel = events.channel(`orders/${userKey}`);

const subscription = channel.subscribe({

next: (event) => {

if (event.type === 'ORDER_STATUS_CHANGED') {

// Update the specific order in state

setOrders((prevOrders) =>

prevOrders.map((order) =>

order.id === event.order_id

? { ...order, status: event.status, updated_at: event.updated_at }

: order

)

);

// Show notification for ready orders

if (event.status === 'ready') {

new Notification(`${event.drink_name} is ready!`);

}

}

},

error: (error) => {

console.error('Subscription error:', error);

setConnected(false);

}

});

setConnected(true);

// Cleanup on unmount

return () => {

subscription.unsubscribe();

setConnected(false);

};

}, [userKey]);

return { orders, setOrders, connected };

}Using the hook in a component is clean.

function OrdersPage({ userKey }: { userKey: string }) {

const { orders, setOrders, connected } = useRealtimeOrders(userKey);

// Fetch initial orders on mount

useEffect(() => {

async function loadOrders() {

const response = await fetch('/api/orders', {

headers: { 'Authorization': `Bearer ${accessToken}` }

});

const data = await response.json();

setOrders(data.orders);

}

loadOrders();

}, [userKey, setOrders]);

return (

<div>

<div className="connection-status">

{connected ? '🟢 Live' : '🔴 Offline'}

</div>

{orders.map(order => (

<OrderCard key={order.id} order={order} />

))}

</div>

);

}The hook handles subscription lifecycle automatically. When the component mounts, it subscribes. When it unmounts, it unsubscribes. The connected state shows users whether they're receiving live updates.

Admin dashboard subscription

The admin dashboard subscribes to the admin/new-orders channel.

function AdminDashboard() {

const [pendingOrders, setPendingOrders] = useState<Order[]>([]);

useEffect(() => {

const subscription = events.channel('admin/new-orders').subscribe({

next: (event) => {

if (event.type === 'NEW_ORDER') {

setPendingOrders(prev => [{

id: event.order_id,

drink_name: event.drink_name,

username: event.username,

status: 'pending',

created_at: event.created_at

}, ...prev]);

}

}

});

return () => subscription.unsubscribe();

}, []);

// Render pending orders...

}New orders appear instantly without polling.

Reconnection and reliability

AppSync Events handles reconnection automatically. If a client loses connectivity, AppSync tries to reconnect. When the connection is re-established, the subscription resumes.

But here's an important caveat: Events published while the client was disconnected are lost. AppSync Events is ephemeral. It doesn't queue messages or replay missed events. Because of this, I treat the database as the source of truth and AppSync as the speed layer.

The real-time updates are there to make the UI feel snappy and responsive while the guest is actively using the app. If the connection drops, the Amplify library handles the reconnection logic automatically. However, since we know messages aren't queued, the app needs a way to catch up.

Whenever the app recovers from an offline state or the guest manually refreshes, the frontend should trigger a quick GET /orders request to the REST API. This ensures that even if they missed a live notification, the screen will always sync up with the actual state of the database.

It is a "best of both worlds" approach. You get the instant, "wow" factor of a live update when things are working perfectly, but you have the reliability of a traditional database to fall back on if the Wi-Fi at the party gets a bit spotty.

What's next

The foundation and ordering flow are complete. Guests can browse drinks, register with invite codes, place orders, and get real-time updates when their drinks are ready. I can manage the menu, view orders, and update order status. Everything works, and it works well.

But the AI piece is still missing. In Part 3, I'll add the features that make this an AI bartender instead of just a digital menu. AI-powered drink recommendations based on taste preferences. Conversational ordering through a chat interface. Image generation for custom drink photos using Amazon Bedrock Nova Canvas. All integrated with the foundation we've built.

Part 3 is coming soon. Follow me on LinkedIn so you don't miss it.

Final words

Real-time updates used to be hard. WebSockets, connection management, broadcasting, scaling. Now AppSync Events handles it all. You publish from Lambda, clients subscribe, and AppSync routes events. That's it.

The self-signed JWT pattern is equally straightforward. Generate an RSA key pair, sign tokens in one Lambda, verify them in another. No Cognito overhead for temporary users, just simple cryptography.

The result is a complete ordering system that feels fast and responsive. Guests register in seconds, place orders with one tap, and get notified the instant their drink is ready. No polling, no manual refreshing, no friction.

The full code is on GitHub. Check out my other posts on jimmydqv.com for more serverless patterns.

Now Go Build!