Building a Serverless AI Bartender - Part 1: Stop Being the Menu

My biggest interests and hobbies are around food and drinks, and I love mixing cocktails at home.

There's something strangely satisfying about mixing that perfect Negroni or shaking up a proper Whiskey Sour. But when I host parties, I face the same problem every time, I become the human menu. People never know what they want, even though I come equipped with a fully stocked bar, so in the end they tend to pick the same old cocktails that they always do.

This New Years eve we were heading to some friends for a party, and basically as always, they asked if I could mix cocktails during the evening. Of course I could do that, but I needed some form of drink menu that people could choose from, I was not going to bring my entire setup with me, only almost...

So, my initial plan was to just print it on paper and people could choose from that. Then, the engineering in me woke up and What if I create create a serverless drink ordering system?

This is the first post in a three-part series where I build a serverless AI cocktail assistant. Let my guests browse the menu themselves and order what they want directly on their phone. And in the end, also get AI recommendations on what to order, with other words, less work for me.

The full source code is available on GitHub.

Let's get started!

What are we building

A web app where guests can browse my drink menu, place orders, and get AI recommendations. Think of it as a digital menu and bartender assistant combined.

To pull this off, I need a solid foundation that includes a database to store drinks and orders, REST APIs that let the app read and write data, authentication to keep the admin panel secure while letting guests browse freely, and image upload so I can add photos to each drink. All serverless, of course—no servers to manage, just services that scale with demand.

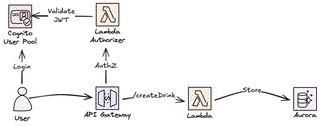

Architecture Overview

In the first part we will cover the foundation. This is the ground that everything stands on, without a proper foundation it will be hard to extend with new features and functionality. We will create the frontend hosting, API hosted by Amazon API Gateway, compute with AWS Lambda, Auth with Amazon Cognito, Amazon S3 for images, Amazon EventBridge for event-driven workflows like AI image prompt generation, and Amazon Aurora DSQL as our primary database.

Aurora DSQL the serverless relational database

For the database, I went with Aurora DSQL. It's a serverless PostgreSQL-compatible database. No provisioning, no connection pools to manage, and it scales automatically.

Why did I go with DSQL? When I started the project I was between using DynamoDB or a DSQL. One important aspect was that the selected database had to be serverless and run without VPC, which eliminates Aurora Serverless. The reason I went for DSQL and a relational model was that I will need a proper search and filtering, on ingredients as an example. DynamoDB is a great key-value store but all data models doesn't fit that.

DSQL gives me several advantages that make it the right choice. It's serverless, I pay only for what I use and it scales to zero when nobody's browsing the menu. Being PostgreSQL compatible means I get proper SQL with search and filtering capabilities built in, essential for querying by ingredients. There's no password management either, as IAM authentication keeps things secure without rotating secrets. And importantly, it works naturally with Lambda's ephemeral connection model. Each Lambda invocation can authenticate independently without managing persistent pools.

Setting Up DSQL

Creating a new DSQL cluster is pretty straightforward. I use CloudFormation to create a DSQL cluster and two IAM roles, one for reading data, one for writing. Why two different roles? Mainly for separation of duty. In this system, 95% of the traffic will be read operations, guests browsing the menu. Only admins perform writes when managing drinks. By splitting the roles, I ensure that the Lambda functions handling guest requests can only read. They physically cannot modify data even if I make an error in the function. The writer role, on the other hand, is restricted to the admin Lambda functions behind the Cognito authorizer. It's a small extra effort that creates a meaningful boundary.

Resources:

DSQLCluster:

Type: AWS::DSQL::Cluster

Properties:

DeletionProtectionEnabled: true

ClusterEndpointEncryptionType: TLS_1_2

# Reader role - used by public API endpoints

DatabaseReaderRole:

Type: AWS::IAM::Role

Properties:

AssumeRolePolicyDocument:

Version: "2012-10-17"

Statement:

- Effect: Allow

Principal:

AWS: !Sub "arn:aws:iam::${AWS::AccountId}:root"

Action: sts:AssumeRole

Policies:

- PolicyName: DSQLReadAccess

PolicyDocument:

Version: "2012-10-17"

Statement:

- Effect: Allow

Action: dsql:DbConnect

Resource: !GetAtt DSQLCluster.Arn

# DatabaseWriterRole follows same patternDatabase roles and permissions

DSQL uses a two-layer permission model. First, you need an IAM role that can connect to the cluster. Second, you need a database role that controls what you can do once connected.

In my setup this is how it works.

- The Lambda function assumes an IAM role, like the

DatabaseReaderRolefrom above, via STS - Using those credentials, the Lambda function calls

dsql.generate_db_connect_auth_token(), this will requiredsql:DbConnectpermission - The Lambda function connects to DSQL using the auth token as password

- DSQL maps the IAM role to a database role which controls table access

Here's the Python code that does this.

def get_auth_token(endpoint: str, region: str, role_arn: str) -> str:

"""Generate DSQL auth token using assumed role credentials."""

# Step 1: Assume the database IAM role

sts = boto3.client("sts", region_name=region)

creds = sts.assume_role(

RoleArn=role_arn,

RoleSessionName="dsql-session"

)["Credentials"]

# Step 2: Create DSQL client with assumed credentials

dsql = boto3.client(

"dsql",

region_name=region,

aws_access_key_id=creds["AccessKeyId"],

aws_secret_access_key=creds["SecretAccessKey"],

aws_session_token=creds["SessionToken"],

)

# Step 3: Generate the auth token (requires dsql:DbConnect permission)

return dsql.generate_db_connect_auth_token(

Hostname=endpoint,

Region=region

)The database role setup looks like this.

-- Create a database role for read-only access

CREATE ROLE lambda_drink_reader WITH LOGIN;

-- Link the IAM role to this database role

AWS IAM GRANT lambda_drink_reader TO 'arn:aws:iam::[ACCOUNT_ID]:role/drink-assistant-data-reader-role';

-- Grant permissions at the database level

GRANT USAGE ON SCHEMA cocktails TO lambda_drink_reader;

GRANT SELECT ON ALL TABLES IN SCHEMA cocktails TO lambda_drink_reader;The writer role follows the same pattern but also grants INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE permissions.

Database Schema

The database schema consists of several tables and indexes, but the primary table is the drinks table. I had to make a few deliberate design choices here. Most importantly, how do I store ingredients?

CREATE SCHEMA IF NOT EXISTS cocktails;

CREATE TABLE cocktails.drinks (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

section_id UUID REFERENCES cocktails.sections(id),

name VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL,

description TEXT,

ingredients JSONB NOT NULL, -- Flexible for varying ingredient counts

recipe_steps TEXT[],

image_url TEXT,

is_active BOOLEAN DEFAULT true

);

-- sections and orders tables follow similar patternsI use JSONB for ingredients because each drink has a wildly different list. A Margarita needs three ingredients like tequila, lime juice, and triple sec. A classic Tiki drink might need eight or more. With a relational model, I'd either need a separate ingredients table with a many-to-one relationship (adding complexity), or create a fixed number of ingredient columns (wasting space or capping the list). JSONB gives me flexibility without sacrificing searchability—PostgreSQL can query inside JSONB fields with proper indexes, so if I later want to search "all drinks with tequila," it's still efficient.

I considered storing ingredients as a simple TEXT field with comma-separated values, but that doesn't scale when I want to add more metadata later, quantity, unit of measurement, substitutes. JSONB future-proofs the schema without requiring migrations.

The permissions gotcha that did cost me hours

As I developed the solution I needed to update tables and create new tables and here's something that caught me off guard with DSQL. I had my database roles set up, everything working perfectly. But after I added a new table for user registration, deployed it, and immediately hit permission errors.

permission denied for table registration_codesThe problem? DSQL doesn't support ALTER DEFAULT PRIVILEGES.

In regular PostgreSQL, you can run something like this.

-- This does NOT work in DSQL

ALTER DEFAULT PRIVILEGES IN SCHEMA cocktails

GRANT SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE ON TABLES TO lambda_drink_writer;This would automatically grant permissions on any future tables. But DSQL doesn't support this command. When you create a new table, your existing database roles have zero access to it until you explicitly grant permissions.

The fix is simple but easy to forget. Every time you add a table, you need a corresponding GRANT statement.

-- New table

CREATE TABLE cocktails.registration_codes (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

code VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL UNIQUE,

expires_at TIMESTAMP NOT NULL,

used_at TIMESTAMP

);

-- Don't forget this!

GRANT SELECT ON cocktails.registration_codes TO lambda_drink_reader;

GRANT SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE ON cocktails.registration_codes TO lambda_drink_writer;I solved this by keeping a dedicated migration file that tracks all table permissions. When I add a new table, I update this file with the explicit grants. It's manual, but it prevents the why can't my Lambda read this table debugging sessions.

Authentication and Authorization

Before diving into the API, let's look at and set up authentication. The system has two types of users with very different access levels. Guests can browse drinks freely, they don't need to prove who they are until they want to place an order. Admins, on the other hand, need full authentication to manage the menu, view all orders, and update order status.

This split means I need both authentication, verifying who you claim to be, and authorization, deciding what you're allowed to do. Admins go through a full Cognito flow with username and password. Guests get a lightweight, invite based registration flow that I'll detail in Part 2.

So Admins need to sign in to perform admin tasks, such as creating new or updating existing drinks.

Cognito User Pool for Admins

Amazon Cognito User Pool will contain and handle admin authentication. It provides a hosted user pool, JWT tokens, and group management without me building any of it.

UserPool:

Type: AWS::Cognito::UserPool

Properties:

UserPoolName: !Sub "${AWS::StackName}-users"

AutoVerifiedAttributes:

- email

Schema:

- Name: email

Required: true

- Name: name

Required: true

UserPoolClient:

Type: AWS::Cognito::UserPoolClient

Properties:

UserPoolId: !Ref UserPool

GenerateSecret: true

AllowedOAuthFlowsUserPoolClient: true

CallbackURLs:

- !Sub "https://${DomainName}/admin/callback"

AllowedOAuthFlows:

- code

AllowedOAuthScopes:

- email

- openid

- profile

SupportedIdentityProviders:

- COGNITO

AccessTokenValidity: 1 # 1 hour

RefreshTokenValidity: 30 # 30 days

AdminGroup:

Type: AWS::Cognito::UserPoolGroup

Properties:

GroupName: admin

UserPoolId: !Ref UserPoolCognito Hosted Login

Instead of building my own login forms, I use Cognito's hosted UI. It handles the entire login flow including username/password, error messages, and password reset, all with a clean, customizable interface.

HostedUserPoolDomain:

Type: AWS::Cognito::UserPoolDomain

Properties:

Domain: !Ref HostedAuthDomainPrefix # e.g., "drink-assistant-auth"

ManagedLoginVersion: 2

UserPoolId: !Ref UserPool

ManagedLoginStyle:

Type: AWS::Cognito::ManagedLoginBranding

Properties:

ClientId: !Ref UserPoolClient

UserPoolId: !Ref UserPool

UseCognitoProvidedValues: true # Use default stylingThe ManagedLoginVersion: 2 gives you the newer, more customizable login experience. The ManagedLoginBranding resource lets you style the login page. I'm using Cognito's defaults here, but you can customize colors, logos, and CSS.

The hosted UI URL follows this pattern.

https://.auth..amazoncognito.com/login

?client_id=

&response_type=code

&scope=email+openid+profile

&redirect_uri=https:///admin/callback The login flow works like this.

- Admin clicks "Login" in the admin panel

- Frontend redirects to Cognito hosted UI

- Admin enters credentials

- Cognito validates and redirects back with an authorization code

- Frontend exchanges code for JWT tokens (access, ID, refresh)

- Access token is stored and sent with API requests

When an admin logs in, Cognito returns a JWT access token. This token contains claims including cognito:groups which lists the user's group memberships. This will be used later when doing an authorization of the admin.

For a deeper dive on authentication and authorization patterns with Cognito, check out my post PEP and PDP for Secure Authorization with Cognito.

REST API with API Gateway

Setting up and creating the REST API is nothing special, we'll use Amazon API Gateway, and I choose the REST version (v1) for the job. There are a few reasons for that, but in this part I'll cover one of them. I need support for API Keys and throttling and as of now the REST version is the only that support that. The API follows a clear separation with public endpoints for guests browsing drinks and placing orders, admin endpoints for managing the menu. Each has different authentication and throttling requirements.

Public endpoints (API key only):

GET /drinks - List all drinks

GET /drinks/{id} - Get drink details

GET /sections - List menu sections

POST /orders - Place an order

GET /orders/{id} - Check order status

Admin endpoints (API key + JWT):

POST /admin/drinks - Create drink

PUT /admin/drinks/{id} - Update drink

DELETE /admin/drinks/{id} - Delete drink

GET /admin/orders - View all orders

PUT /admin/orders/{id} - Update order statusLambda Authorizer for AuthN + AuthZ

API Gateway uses a Lambda authorizer to validate requests. This is where both authentication and authorization happens.

def handler(event, context):

"""Lambda authorizer - handles both AuthN and AuthZ."""

token = extract_bearer_token(event)

# Step 1: Authentication - verify the JWT is valid

claims = validate_token(token) # Checks signature, expiry, issuer

# Step 2: Authorization - check if user has admin role

if "/admin/" in event["methodArn"]:

if "admin" not in claims.get("cognito:groups", []):

return generate_policy(claims["sub"], "Deny", event["methodArn"])

# Both checks passed

return generate_policy(claims["sub"], "Allow", event["methodArn"])The JWT validation fetches Cognito's public keys (JWKS) and verifies.

- Signature - Token wasn't tampered with

- Expiry - Token hasn't expired

- Issuer - Token came from my Cognito user pool

If all checks pass, the authorizer looks at the cognito:groups claim. Admin endpoints require the user to be in the admin group, the authorization check.

Why a Lambda Authorizer?

API Gateway has built-in Cognito authorizers, but they only do authentication. They verify the token is valid but can't check group membership. The Lambda authorizer lets me do both in one step.

The authorizer also passes user context to downstream Lambda functions.

return {

"principalId": claims["sub"],

"policyDocument": { ... },

"context": {

"userId": claims["sub"],

"email": claims["email"],

"role": "admin" if is_admin(claims) else "user"

}

}This context is available in event["requestContext"]["authorizer"] so Lambda functions know who made the request without parsing the JWT again.

Why API Keys for Public Endpoints?

Even public endpoints require an API key. This isn't for authentication, it's for protection and control. API keys link to usage plans with rate limits, giving me fine-grained throttling control. CloudWatch metrics show usage per key, providing visibility into who's calling the API and how often. And if something goes wrong, I can disable a key instantly as a kill switch.

The API key is embedded in the frontend, so it's not secret. But it gives me control over who can call the API and how often.

Usage Plans and Throttling

Different endpoints have different rate limits based on expected usage.

PublicUsagePlan:

Type: AWS::ApiGateway::UsagePlan

Properties:

ApiStages:

- ApiId: !Ref DrinkAssistantApi

Stage: v1

Throttle:

"/drinks/GET":

RateLimit: 100 # requests per second

BurstLimit: 200 # spike allowance

"/orders/POST":

RateLimit: 50 # slower - writes to database

BurstLimit: 100Browsing drinks can happen 100 times per second. Placing orders is limited to 50/second since it involves database writes and event publishing, so I want to be more conservative.

For a house party this is massive overkill. But it's a good habit, and if this ever became a real product, the foundation is there.

API Gateway Caching

The drinks menu rarely changes, but guests browse it constantly. Without caching, every page load hits Lambda and DSQL. With 20 guests refreshing the menu every few seconds, that's unnecessary load and cost.

API Gateway has built-in caching that's surprisingly effective for this scenario.

ApiGateway:

Type: AWS::Serverless::Api

Properties:

StageName: prod

CacheClusterEnabled: true

CacheClusterSize: "0.5" # Smallest size, ~$15/month

MethodSettings:

- HttpMethod: GET

ResourcePath: /drinks

CachingEnabled: true

CacheTtlInSeconds: 3600 # 1 hourNow GET /drinks returns cached responses for 1 hour. The menu doesn't change that often, so this is a reasonable trade-off. But here's the catch, what happens when I add a new drink? Guests would be browsing an outdated menu until the cache expires naturally.

The solution is aggressive invalidation. The createDrink Lambda flushes the entire API cache after saving to the database.

def flush_api_cache():

"""Invalidate API Gateway cache after data changes."""

client = boto3.client("apigateway")

client.flush_stage_cache(

restApiId=os.environ["API_ID"],

stageName="prod"

)This pattern, cache aggressively for reads, invalidate immediately on writes, gives you the best of both worlds: fast page loads for browsing, and instant updates when the menu changes. Note that this approach works well for the menu endpoint because data changes are infrequent and controlled. If I were caching order status or real-time data, I'd either use a shorter TTL or skip caching entirely. The key is matching the cache strategy to how often your data actually changes.

Image Upload with S3

Drink photos go to S3 using pre-signed URLs. This keeps large uploads off Lambda, due to that it has a 10MB request limit.

The flow is straightforward. When an admin wants to upload a drink photo, they request an upload URL from the API. The Lambda function generates a pre-signed PUT URL that's valid for 10 minutes, giving the admin a temporary, scoped permission to upload directly to S3. The admin's browser then uploads the image straight to S3 without touching Lambda at all. Once uploaded, CloudFront serves the image to guests browsing the menu.

The S3 bucket CloudFormation.

ImageBucket:

Type: AWS::S3::Bucket

Properties:

BucketName: !Sub "${AWS::StackName}-images"

CorsConfiguration:

CorsRules:

- AllowedOrigins:

- "*"

AllowedMethods:

- PUT

- GET

AllowedHeaders:

- "*"

MaxAge: 3600

PublicAccessBlockConfiguration:

BlockPublicAcls: true

BlockPublicPolicy: true

IgnorePublicAcls: true

RestrictPublicBuckets: true

ImageBucketPolicy:

Type: AWS::S3::BucketPolicy

Properties:

Bucket: !Ref ImageBucket

PolicyDocument:

Statement:

- Effect: Allow

Principal:

Service: cloudfront.amazonaws.com

Action: s3:GetObject

Resource: !Sub "${ImageBucket.Arn}/*"

Condition:

StringEquals:

AWS:SourceArn: !Sub "arn:aws:cloudfront::${AWS::AccountId}:distribution/${CloudFrontDistribution}"And the Lambda that generates presigned URLs.

import boto3

import json

import uuid

import os

from aws_lambda_powertools import Logger

logger = Logger()

s3_client = boto3.client("s3")

def handler(event, context):

"""Generate presigned URL for image upload."""

try:

body = json.loads(event["body"])

filename = body["filename"]

content_type = body.get("content_type", "image/jpeg")

# Generate unique key

s3_key = f"drink-images/{uuid.uuid4()}-{filename}"

# Generate presigned URL (valid 10 minutes)

presigned_url = s3_client.generate_presigned_url(

"put_object",

Params={

"Bucket": os.environ["IMAGE_BUCKET"],

"Key": s3_key,

"ContentType": content_type

},

ExpiresIn=600

)

# CloudFront URL for accessing the image

cloudfront_url = f"https://{os.environ['CLOUDFRONT_DOMAIN']}/{s3_key}"

logger.info(f"Generated upload URL for {filename}")

return {

"statusCode": 200,

"body": json.dumps({

"upload_url": presigned_url,

"image_url": cloudfront_url,

"key": s3_key

})

}

except Exception as e:

logger.exception("Error generating presigned URL")

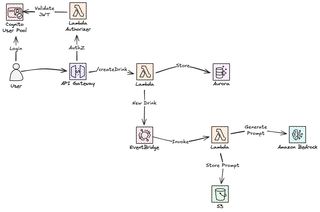

return {"statusCode": 500, "body": json.dumps({"error": str(e)})}Event-Driven Image Prompt Generation

Here's where it gets interesting, and the part and solutions I normally build and write about. When I add a new drink, I want an AI-generated image prompt ready for when I eventually create the drink photo. Instead of manually writing prompts, I let Amazon Bedrock generate them based on the drink's name and ingredients.

The key is decoupling at its finest. I could have called Bedrock directly from the createDrink Lambda, but that would add latency to the API response since the admin has to wait for AI generation. EventBridge solves this elegantly. The API returns immediately after the database save, keeping response times fast. The event bus handles the prompt generation asynchronously, and if Bedrock is slow or fails temporarily, EventBridge automatically retries. This loose coupling also means I can easily extend the system later by adding more event listeners for notifications or analytics without touching the API code at all.

Why a Custom Event Bus?

I use a dedicated event bus instead of the default AWS bus.

DrinkAssistantEventBus:

Type: AWS::Events::EventBus

Properties:

Name: drink-assistant-eventsWhy not just use the default bus? Three reasons.

- Isolation - My application events don't mix with AWS service events (CloudTrail, etc.)

- Permissions - I can grant specific IAM roles access to only this bus

- Filtering - Rules only see events from my application, making patterns simpler

For a small project this might seem like overkill, but it's a good habit. When you have multiple applications publishing events, a dedicated bus per domain keeps things clean.

The Event Flow

The createDrink Lambda function publishes an event after saving to the database.

def publish_drink_created(drink: dict) -> bool:

"""Publish DrinkCreated event to EventBridge."""

events_client = boto3.client("events")

event_detail = {

"metadata": {

"event_type": "DRINK_CREATED",

"version": "1.0",

"timestamp": datetime.utcnow().isoformat() + "Z",

},

"data": {

"drink_id": drink["id"],

"name": drink["name"],

"description": drink.get("description", ""),

"ingredients": drink.get("ingredients", []),

},

}

events_client.put_events(

Entries=[{

"Source": "drink-assistant.api",

"DetailType": "DrinkCreated",

"Detail": json.dumps(event_detail),

"EventBusName": os.environ["DRINK_EVENT_BUS_NAME"],

}]

)The event is fire-and-forget. If it fails, we log it but don't fail the API call. The drink is already saved.

Generating the Prompt with Bedrock

Here's where prompt engineering becomes critical. I initially tried a generic system prompt like "Create an image prompt for a cocktail photograph" and let it loose. The results were functional but uninspired—generic descriptions of drinks in generic glassware under generic lighting. Not terrible, but not aligned with my vision of Nordic minimalism.

I chose Amazon Bedrock Nova Pro for this task because it balances cost and quality. Nova Pro is cheaper than Claude while still producing coherent, detailed outputs. The model doesn't hallucinate wildly, and for image prompts, I don't need bleeding, edge reasoning, I need consistent, predictable outputs that an image generation model can work with.

The real work is in the prompts. The system prompt establishes the photographer's persona and perspective. The user prompt provides specific constraints and aesthetic guidance. Here's the evolution:

First attempt (too generic):

System: "You are a photographer. Generate an image prompt for a cocktail."

User: "Cocktail: Negroni. Ingredients: Campari, gin, vermouth."

Result: "A Negroni cocktail in a crystal glass, garnished with an orange twist, photographed in a studio setting with professional lighting."

This works, but it's generic—could describe any cocktail photo.

Second attempt (more specific):

System: "You are a photographer specializing in beverage photography. Create a detailed, photorealistic prompt for a cocktail photograph."

User: "Cocktail: Negroni. Generate a prompt emphasizing minimalist, Nordic aesthetic, professional studio lighting."

Result: "A Negroni in a rocks glass, minimally garnished with an orange twist, against a soft gray background. Clean studio lighting emphasizing the drink's deep red color and clarity. Minimalist composition. Professional photography."

Better! More specific, but the Nordic aesthetic still isn't clear enough.

Final version (what I actually use):

def generate_prompt(drink: dict) -> str:

"""Generate image prompt using Bedrock Nova Pro."""

bedrock = boto3.client("bedrock-runtime")

# The system prompt establishes photographer expertise and style

system_prompt = """You are an expert photographer specializing in

beverage photography for luxury brands. You create detailed, photorealistic

prompts for studio photographs. Your style emphasizes Nordic minimalism:

clean lines, soft lighting, neutral backgrounds, and minimal garnishes.

Every element in the frame has purpose."""

# The user prompt provides specific drink info and reinforces aesthetic

user_prompt = f"""

Cocktail: {drink['name']}

Description: {drink['description']}

Ingredients: {', '.join(drink['ingredients'])}

Generate a detailed image prompt (2-3 sentences) for a photorealistic

studio photograph with these requirements:

- Glassware: appropriate type for this cocktail's style

- Color/clarity: describe the drink's visual appearance

- Garnish: minimal, elegant, purposeful

- Aesthetic: Nordic minimalism—soft shadows, neutral background (white or soft gray),

professional studio lighting that shows the drink's true colors

- Composition: centered, clean, no clutter

Output: Just the prompt, no preamble.

"""

response = bedrock.invoke_model(

modelId="eu.amazon.nova-pro-v1:0",

body=json.dumps({

"messages": [{"role": "user", "content": [{"text": user_prompt}]}],

"inferenceConfig": {

"temperature": 0.7, # Balanced: creative but consistent

"maxTokens": 300 # Enough for 2-3 sentences

}

})

)

return json.loads(response["body"].read())["output"]["message"]["content"][0]["text"]The temperature of 0.7 strikes a balance. Higher (closer to 1.0) would make each prompt more random and creative, but less consistent across drinks. Lower (closer to 0) would be repetitive. At 0.7, each prompt is unique but predictable enough that an image generation model gets the aesthetic right. The maxTokens: 300 is set specifically because Nova Canvas, the image generation model I tested during the project, has a 300-token limit for prompts. This forces the text generation to stay concise while still being descriptive.

This expansion of the system prompt—explaining that I want Nordic minimalism specifically, describing what that means (soft shadows, neutral backgrounds, minimal garnish), was the key breakthrough. The first time I generated prompts with this version, the results were finally aligned with my vision, clean, minimal, premium-looking cocktail photography.

The prompt is saved to S3 for later use when I actually generate the image (maybe with Nova Canvas in a future version).

Extensibility

This pattern scales well. When I add image generation, it's just another rule listening to the same event. No changes to the API needed.

What's Next

The foundation is done. Guests can browse the menu, admins can manage drinks. But guests can't actually place orders yet, they need a way to identify themselves without creating full accounts.

In Part 2, I'll build the complete ordering flow.

- Guest registration with invite codes and self-signed JWTs

- Order placement with a custom Lambda authorizer

- Real-time notifications using AWS AppSync Events - when I mark a drink ready, guests see it instantly

Stay tuned and follow me on LinkedIn so you don't miss it!

Final Words

This foundation might not be the flashiest part of the project, but it's the groundwork that makes everything else possible. Database, APIs, authentication, event-driven workflows. It's all here, ready to support the real magic.

Because this is just the beginning. The AI cocktail assistant is the goal, and that's where it gets interesting. AI recommendations based on taste preferences, image generation for drink photos, real-time order updates, maybe even conversational ordering. The foundation is done. Now comes the fun part.

That's what I love about serverless and managed services like DSQL, Cognito, EventBridge, and Bedrock. They handle the undifferentiated heavy lifting so you can move fast on the foundation and spend your time on what actually makes the project unique. The AI features. The user experience. The things that make people say "that's cool."

Part 2 is coming soon. Guest registration, ordering flow, and real-time notifications. Stay tuned.

Check out my other posts on jimmydqv.com and follow me on X for more serverless content.

As Werner says, Now Go Build!